SUMMARY

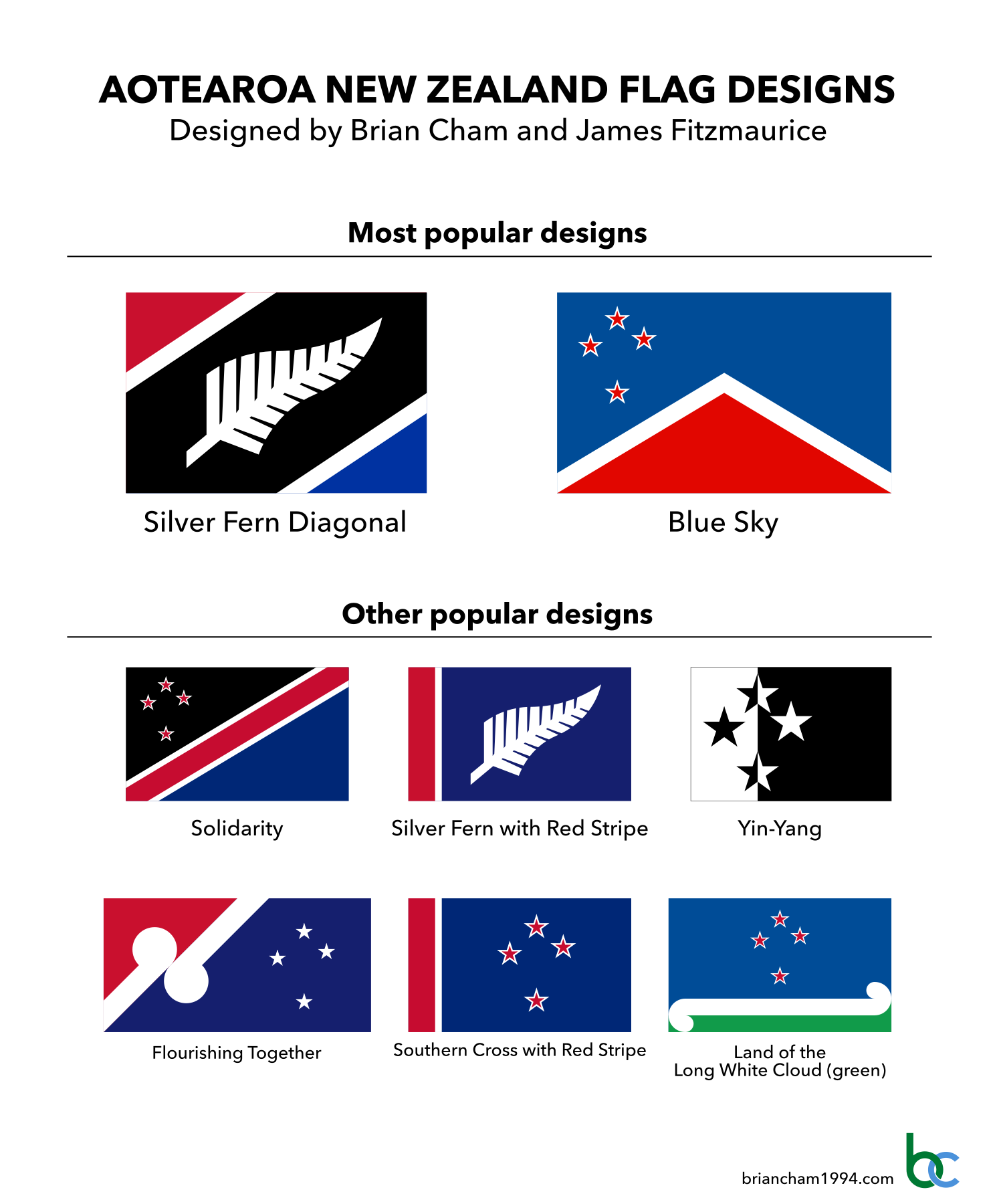

Here are the flag concepts for Aotearoa New Zealand that I and James Fitzmaurice designed over the years.

These flags are based on extensive research and analysis. We believe our designs surpass those presented in the unsuccessful 2016 national flag referendum, because they actually look like flags (rather than logos or souvenirs), the symbolism is intuitive, recognisable and familiar, they have wide appeal, and they are memorable. They pass the tests that other proposals fail. They also capture the symbolic themes that reflect how the New Zealanders feel about the country, and not just our personal preferences. For more about our extensive design methodology, continue to the “Design Process” section.

Each flag has high-resolution images, commentary, mock-ups and construction sheet. To read more about specific flags, use the table of contents to skip the corresponding section.

Since we presented these in 2022, these flags have been featured in the Flagged for Content podcast. Blue Sky was featured in an award-winning presentation at NAVA 55, while Silver Fern Diagonal came fifth place in a 2024 international flag poll on Flag Session.

Vector files available on request.

CONTENTS

3.2 Silver Fern with Red Stripe

3.5 Southern Cross with Red Stripe

3.6 Land of the Long White Cloud (green)

4. Acknowledgements

References

1. DESIGN PROCESS

1.1 Overall Methodology

What we didn’t do: Just sit down and design a good New Zealand flag.

Why we didn’t do this: Even with my and James’ previous vexillological expertise, a naive process would just result in reinventing the wheel, repeating the mistakes of the past and confusing our intuitive preferences with those of the general population. This is what almost every other designer did and why they failed.

What we did instead:

We adopted the ultimate guiding principle of maximum feasibility. Our single focus and criterion of success was that the flag design must have the highest probability of winning a vote against the current flag. We shed the popular mindset where we were making a personal artistic expression and replaced it with the mindset where we were analysing and capturing the symbolism of the nation’s collective unconscious that would result in the most public resonance. Flags are supposed to express a group’s identity, rather than prescribe it, otherwise the designs cannot achieve the wide appeal that we need. Instead of activating the aesthetic part of our brain and asked what symbolism resonates with us, we activated the sympathy part of our brain and asked what resonates with others.

Anyone can design a flag and feel that it would be a popular and feasible choice but we put in the hard work to make our decisions grounded. Here are some techniques we used:

- Evaluate all (yes, all) existing proposals. What are the best and worst features? What are common symbols, colours and themes? How were they received by commenters? Why were some more popular than others? From this we constructed a rudimentary regression analysis to capture and predict which design elements and features were associated with higher public appeal.

- Study New Zealand themed insignia, logos and graphics. What are common symbols, colours and themes? Why?

- Research surveys and campaigns. What are the preferences among the public, and in what proportions?

- Survey a real spread of people throughout the design process, not just the people around us. Consulting only the people we knew personally would be short-sighted and misleading. We also conducted some memory testing on these people to see which designs were most memorable. While this process was not as scientific as we would have liked, some clear patterns emerged.

The more artistically inclined may feel this approach is too calculated and soulless, almost like a market research exercise. However, it was deemed necessary for reasons pragmatic (because that’s how referendum voting works and presenting a design with no actual chances would just be a waste of everyone’s time*), creative (because it focuses our thoughts and research into a specific direction) and democratic (because the design would appeal to most of the national population; isn’t that the point?).

Designs in the running to become the actual national flag deserve this level of certainty and effort – we are trying to design the New Zealand flag, not a New Zealand flag.

* i.e. what actually happened in the referendum, but that’s a story for another day.

1.2 The Six Deal-Breakers

Update: This section has been expanded into its own presentation and article entitled The Six Little-Known Deal-Breakers of Bad Flag Design. It was presented at NAVA’s 55th annual conference where it got an Honorable Mention for the Driver Award.

We were aware that no previous proposal was loved enough to be a worthy contender to the current flag, so we consciously analysed the commentary behind them all and identified the common pitfalls. This way, we could learn from everyone else’s mistakes and completely transcend them. Listed below are the deal-breakers that afflict so many proposals. Even the official referendum selection falls into these!

Generally bad flag design — The classic sins. Too complicated, too many colours, too many elements, irrelevant symbolism, too similar to other flags, the inclusion of writing, maps or gradients, and so on.

Looks like a logo, not a flag — Most proposals (we would say over ninety percent of them) look like modern art pieces, corporate logos or political statements stuck into a rectangle. Any appeal of these designs disappear if we imagine them actually fluttering on a flagpole alongside other national flags. The design should have a classic, timeless quality rather than an ephemeral, flashy quality. We posed a thought experiment—If you claimed that your design was from fifty years ago and that you had actually rediscovered rather than created it, would anyone believe you?

Cheesy souvenir — A subset of “looks like a logo, not a flag”. Designs can evoke a feeling of cringe and contempt if they look too offbeat, informal or “un-flag-like”. This is subjective – for some, the silver fern is cheesy; for others, the silver fern is conventional.

Mystery symbolism — Roger Ebert once declared, “If you have to ask what it symbolizes, it didn’t.” Flag design is not like conceptual art with its invented imagery and lofty explanations, it’s more like advertising which uses a culture’s shared visual language to intuitively resonate with the audience at first glance. We posed a thought experiment—If your design were transported back in time by fifty years without any accompanying context, would the average person on the street immediately be able to reckon that it’s a New Zealand flag proposal and what everything represents? A similar thought experiment—If your design is submitted to Reverse Google Image Search, is it successfully labelled as “New Zealand”? (this is something we actually tried during our design process)

Designing for yourself – These designers made the mistake of designing for themselves, not for the general public. These designs focus on only one symbolic theme (see the explanation in the next section) at the utter exclusion of other preferences, which is essentially self-sabotage and negates the possibility of general public appeal. Different themes of national identity appeal to different people. They’re not wrong. They’re just not you.

Too radical — These designers wipe the slate clean and aim for a revolutionary design with no established symbolism. This is also self-sabotage. The vote would be held by everyone, and a substantial amount of the population is intimately attached to established symbolism. Flags are supposed to express a group’s identity, rather than prescribe it, otherwise the designs cannot achieve the wide appeal that we need.

It’s boring, but it works — Either James or I once critiqued a particularly minimalist flag proposal as “a bland vanilla design that just appeals weakly to everybody without really rousing anyone”. There is such a thing as a flag being too simple. There is such a thing as trying to satisfy everybody and ending up satisfying nobody. A design which is dull, uninspiring and typical will backfire, not grab attention, not stick in the memory and not have support.

We strove to avoid these deal-breakers and achieve their polar opposites.

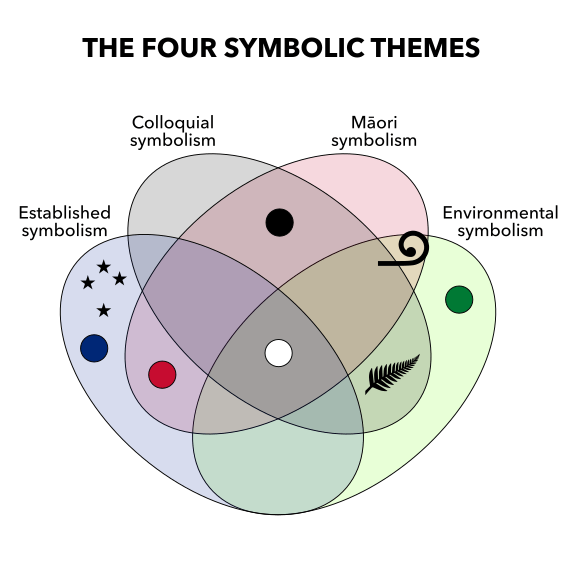

1.3 The Four Symbolic Themes

We were aware that any single individual’s idea of New Zealand identity is subjective and short-sighted, so we researched how the nation as a whole perceives itself. We comprehensively analysed all the existing symbolism, flag proposals, responses and preferences out there. As a result, we identified four themes of national symbolism, named as below:

- “Established” – Symbols and colours associated with the current flag.

- “Colloquial” – Symbols and colours associated with informal, colloquial, local culture.

- “Māori” – Symbols and colours associated with the indigenous culture.

- “Environmental” – Symbols and colours associated with the environment.

The symbols and colours associated with each symbolic theme are summarised in the Euler diagram below.

The four symbolic themes of New Zealand graphical identity.

At the same time, social scientists have determined the core components of New Zealand’s national identity using extensive, empirical, nationwide studies. Sibley, Hoverd, & Liu’s (2011) study uncovered four facets, named as below:

- “Anglo-NZ (Post-Colonial) Ancestry” – Ideas about the British cultural and historical legacy as part of the country’s foundation.

- “Rugby/Sporting Culture” – Ideas about national sports teams as universally popular expressions of national unity and ambition.

- “Bicultural Awareness” – Ideas about Māori cultural and history as part of the country’s foundation.

- “Liberal Democratic Values” – Ideas about egalitarianism and mutual respect for cultures, religions and the environment as fundamental values of modern society.

Interestingly, these four facets corresponded roughly with the four themes from our own analysis, suggesting that it is well grounded. Our inquiry also revealed that each symbolic theme has particular advantages and disadvantages which we needed to keep in mind throughout the design process.

We strove to harmoniously appeal to multiple themes and facets of national identity, harness the advantages of each one and avoid the disadvantages of each one. This would ensure that our designs truly represent the nation and resonate with the most people. At the same time, the designs must still remain simple and elegant. Most importantly, we treated the “established” symbolic theme as the fundamental basis of all designs to ensure the most overall resonance.

Details of each symbolic theme are explained below.

1.3.1 Established symbolism

The “established” symbolic category includes symbols and colours associated with the current flag. This corresponds to the “Anglo-NZ (Post-Colonial) Ancestry” facet from Sibley, Hoverd, & Liu’s (2011) study.

Specific design elements include:

- The red-white-blue colour scheme

- The southern cross

- Layouts that recall the flag of the United Kingdom, i.e. blue fields with red bars and white fimbriation.

Advantages:

- A lot of people are intimately attached to current symbolism and find it pleasingly familiar (refer to the mere exposure effect).

- Establishes continuity and carries over current symbolism.

- Formal feel.

- Historical and cultural significance.

- British representation.

- Appeals to the many “swing voters” who are attached to the symbolism in the current flag.

- Numerically speaking, our regression analysis shows that designs with more of this established symbolism get more support.

- Sibley, Hoverd, & Duckitt’s (2011) psychological study of subconscious graphical influences show that this symbolic theme is more emotionally salient than the others.

Disadvantages:

- Can feel too boring, uninspired, safe and soulless.

- Not as distinct as the purely local symbols like the silver fern.

- Aesthetically, the southern cross does not make a good focal point as it is too “empty” and spread out to be a bold or iconic symbol.

- Osborne, Lees-Marshment, & van der Linden’s (2016) study of New Zealand attitudes showed that a majority of respondents had a lukewarm or low support for the Commonwealth of Nations in relation to core national identity.

1.3.2 Colloquial symbolism

The “colloquial” symbolic theme includes symbols and colours associated with informal, colloquial, local culture. This corresponds to the “Rugby/Sporting Culture” facet from Sibley, Hoverd, & Liu’s (2011) study.

Specific design elements include:

- The black-white colour scheme

- The silver fern

Advantages:

- Unique to New Zealand.

- The silver fern is the best polling design element (Cheng, 2014).

- De facto national colours/emblems that arose from local circumstances. These are very common in New Zealand themed logos and graphics.

- Symbolism is neutral and applies to all people (like Canada’s maple leaf).

- Osborne, et al.’s (2016) study of New Zealand attitudes showed that a majority of respondents (89.2%) had a high support for sports in relation to core national identity.

Disadvantages:

- Can feel too informal, too trendy, too cheesy, too associated with sporting teams (especially the All Blacks) and souvenirs and thus not appropriate for a formal national symbol.

- These were the most contentious design elements in existing flag proposals. The very presence of black or the silver fern put off some respondents; the presence of both black and the silver fern was an absolute deal-breaker for some.

- The black-white colour scheme by itself is dour or reminds some of pirates or ISIS.

- The silver fern is visually very complex and fiddly for a flag.

- Sibley, Hoverd & Duckitt’s (2011) psychological study of subconscious graphical influences show that silver ferns are less emotionally salient than the established symbolism.

1.3.3 Māori symbolism

The “Maori” symbolic theme includes symbols and colours associated with the indigenous culture. This corresponds to the “Bicultural Awareness” facet from Sibley, Hoverd, & Liu’s (2011) study.

Specific design elements include:

- The black-white-red colour scheme

- The colour red in itself if dominant

- The Tino Rangatiratanga flag

- Māori patterns, especially the koru

Advantages:

- Unique to New Zealand

- Historical and cultural significance

- Indigenous representation

- Māori culture is already incorporated and accepted into mainstream, e.g. the coat of arms, haka, national anthem, symbols on coinage and banknotes, Air New Zealand logo and so on.

- Indigenous rights is a key factor that distinguishes New Zealand and its identity from other Western post-colonial nations (i.e. Australia, Canada, USA).

Disadvantages:

- If this theme is too dominant, especially elements of the Tino Rangatiratanga flag itself, it can feel sectarian, ignoring British history or ignoring a multicultural reality.

- Numerically speaking, our regression analysis shows that designs with the koru get far less support than the established symbols.

- Osborne, et al.’s (2016) study of New Zealand attitudes showed that Māori rights, in relation to core national identity, was one of the most polarising socio-cultural attitudes. Overall, a slight majority of respondents (59.2%) expressed a low support for this topic. However, 75.3% agreed with the statement “Māori culture is something that all New Zealanders can take pride in, no matter their background”.

1.3.4 Environmental symbolism

The “environmental” symbolic theme includes symbols and colours associated with the environment. This corresponds to the “Liberal Democratic Values” facet from Sibley, Hoverd, & Liu’s (2011) study, since this facet includes environmental values as well.

Specific design elements include:

- Green

- The silver fern

- The koru

- The kiwi

- Landscapes

Advantages:

- Expresses New Zealand’s “clean green” image

- Some of these elements are unique to New Zealand

- Positive and fresh feel

- The silver fern is the best polling design element (Cheng, 2014).

- Future-proof

- Symbolism is neutral and applies to all people (like Canada’s maple leaf).

Disadvantages:

- Can feel too “hippie”, trendy or informal and thus not appropriate for a formal national symbol.

- Some feel that “clean green” image is just artificial marketing hype writ large.

- Silver fern is visually very complex and fiddly for a flag. Sibley, Hoverd & Duckitt’s (2011) study of subconscious graphical influences show that silver ferns are less emotionally salient than the established symbolism.

- Numerically speaking, our regression analysis shows that designs with green and koru get far less support than the established symbols.

2. MOST POPULAR DESIGNS

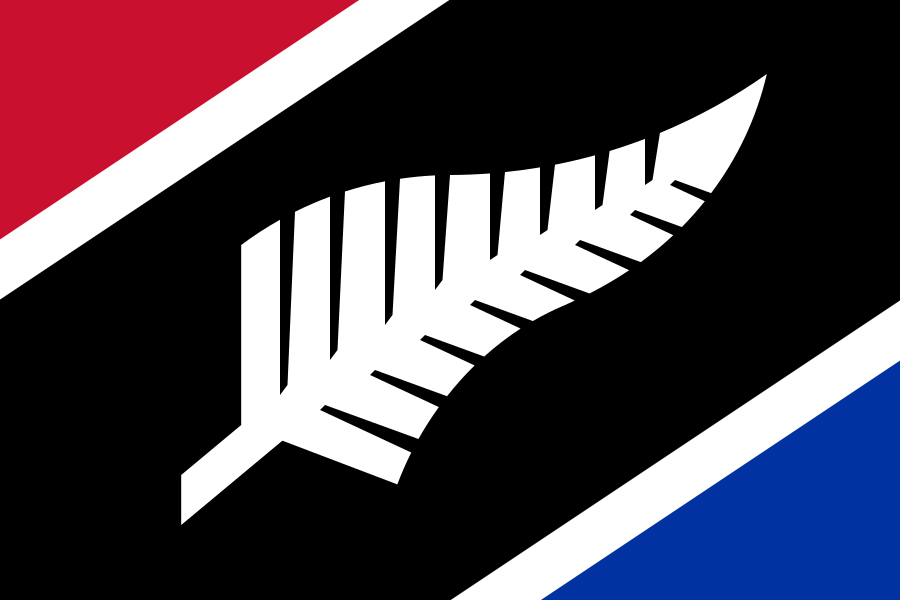

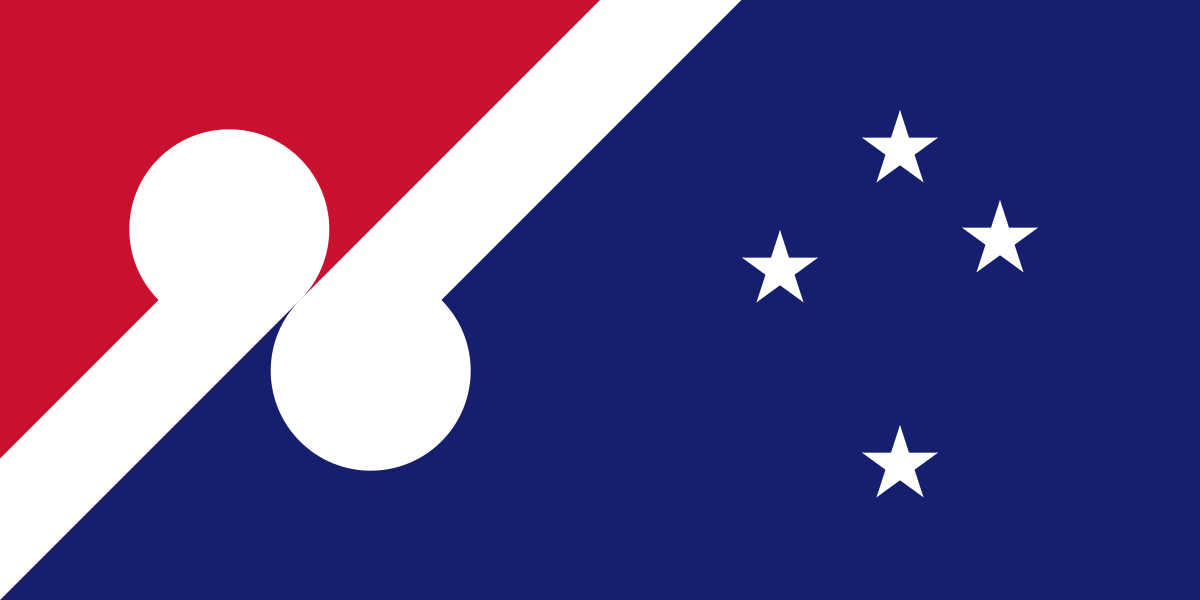

2.1 Silver Fern Diagonal

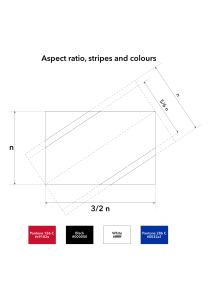

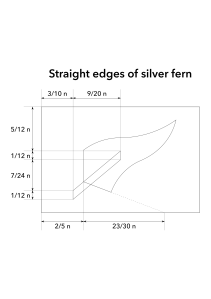

This design used to be the second most popular of our designs, but has gradually become the most popular. It is based on the well-known silver fern on black, but with key modifications

- We added red and blue diagonal stripes to represent the two foundational cultures that signed the Treaty of Waitangi, with red, white and black from the Māori flag and red, white and blue from the British flag. This symbolises the country’s intermixed cultures and history in a visually striking and harmonious way, averting any claim that the silver fern is just a “sporting flag”.

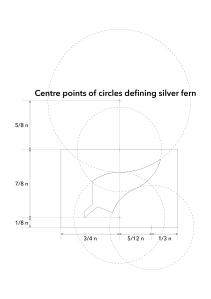

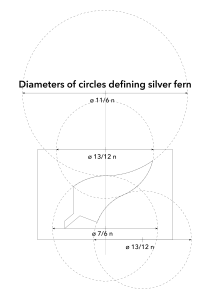

- The form of the silver fern was constructed by overlaying many different silver fern symbols and tracing the average shape. This makes the silver fern as generic as possible, so it doesn’t resemble any specific logo or sporting team emblem.

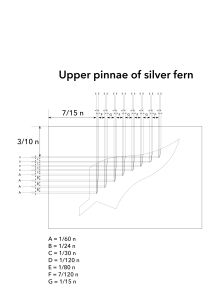

- The form of the silver fern was also highly simplified, just like the simplified maple leaf on the flag of Canada. It has a smooth outline and few pinnae (the fiddly bits sticking out on each side), making the profile distinct at a distance and easier to construct.

This design blew away the others in our memory testing. Although this was not a scientific process, the difference was quite striking. We suspect that this is because of the diagonal layout. In the psychology of perception, “orientation selectivity” means that purely horizontal and vertical stimuli are treated as “background” elements and ignored by the cerebral cortex, but tilted stimuli elicit stronger attention (Hubel & Wiesel, 2004). Also, in the psychology of memory, concepts are more memorable if they are based on something familiar but with a slightly counter-intuitive twist (Barett & Nyhof, 2001), which applies to the way we modified the silver fern design.

Silver Fern Diagonal

Mock-ups for Silver Fern Diagonal

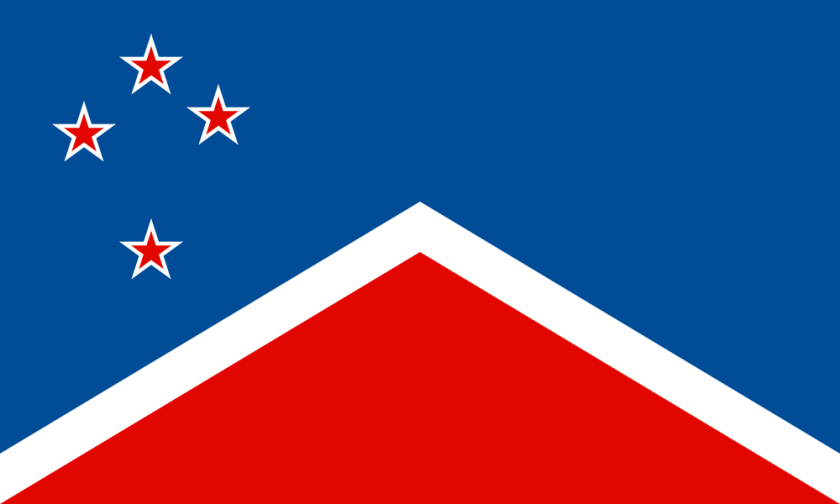

2.2 Blue Sky

This flag was designed to be the most effective NZ flag proposal for the referendum, surpassing the other designs by incorporating all the public feedback. It actually looks like a flag rather than a logo or souvenir, the symbolism doesn’t need to be explained, it has wide appeal and resonance, and it is very memorable based on our memory testing. Blue Sky formed part of the award-winning Six Deal-Breakers of Bad Flag Design presentation at NAVA 55, where it was used as an example of a flag that is specifically designed to counter-act those deal-breakers.

Funnily enough, we didn’t enter this flag into the referendum contest because James objected to the geometric style. Afterwards, I put it on the website out of public demand because everyone loved it so much!

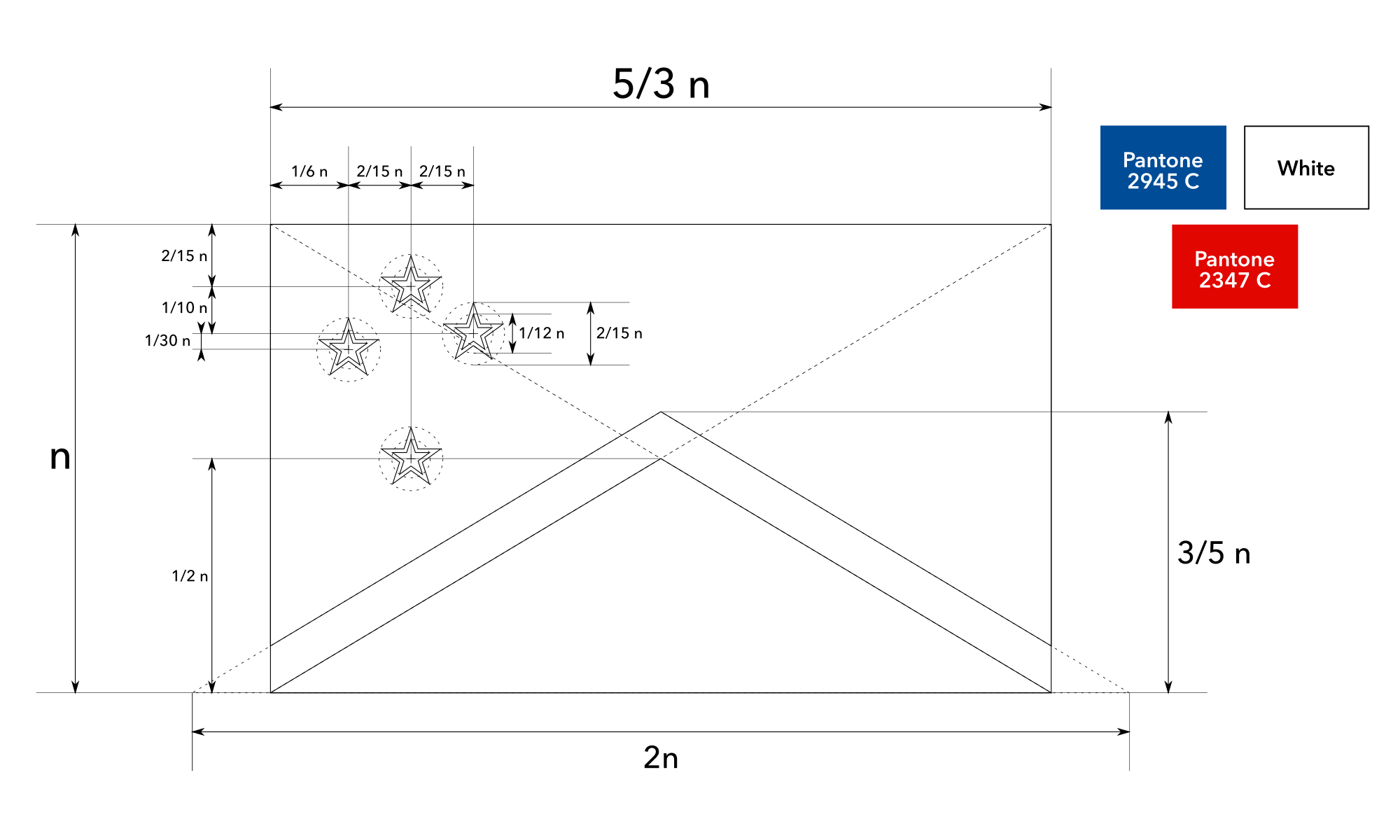

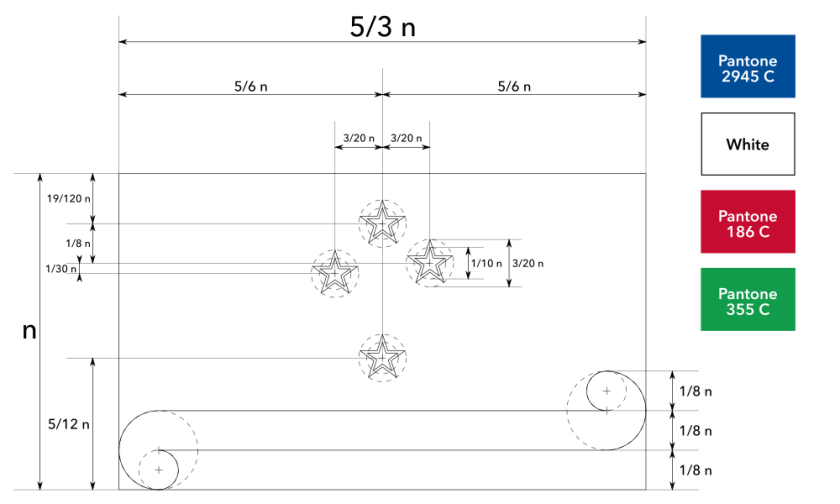

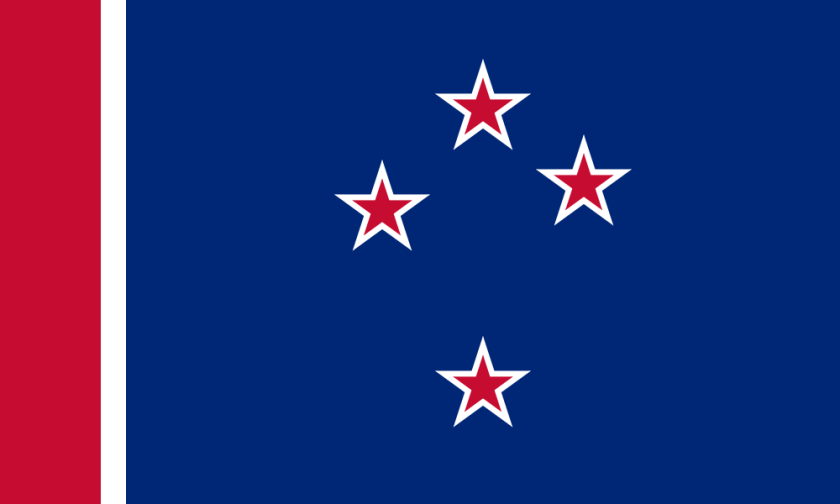

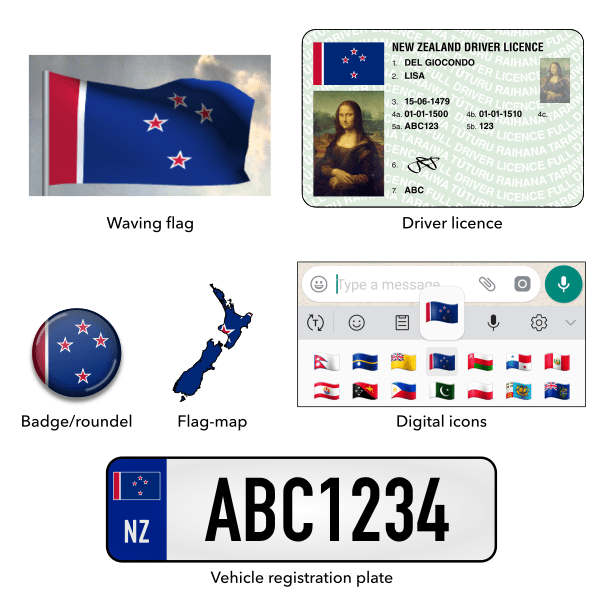

Blue Sky, White Mist and a Wholly Red Earth

Mock-ups for Blue Sky, White Mist and a Wholly Red Earth

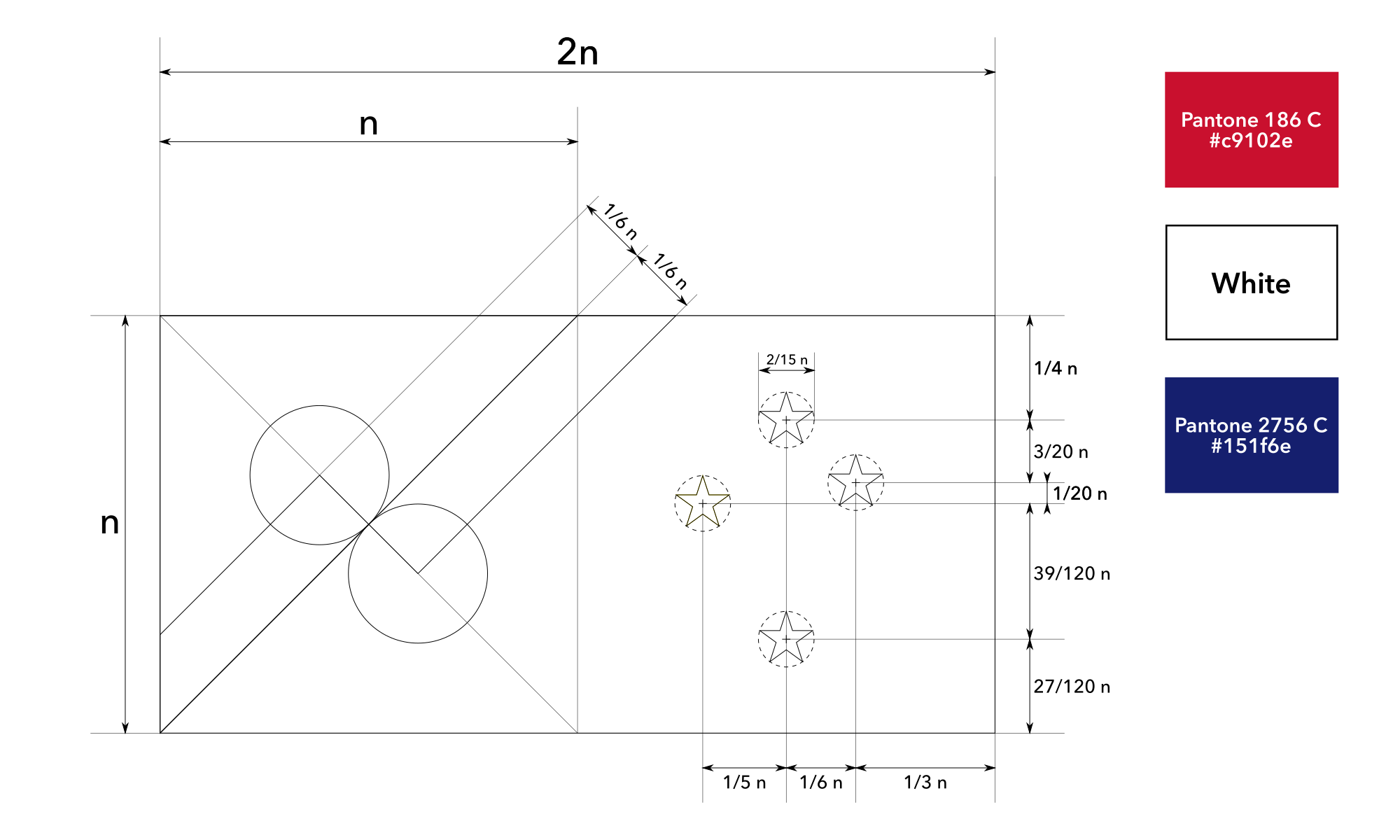

Construction sheet for Blue Sky, White Mist and a Wholly Red Earth

3. OTHER DESIGN PROPOSALS

These are roughly in order, starting from the most popular.

3.1 Solidarity

This was one of our most popular designs, but personally, it’s one of my least favourites. Incidentally, it’s the first design we ever made.

Solidarity

Mock-ups for Solidarity

Construction sheet for Solidarity

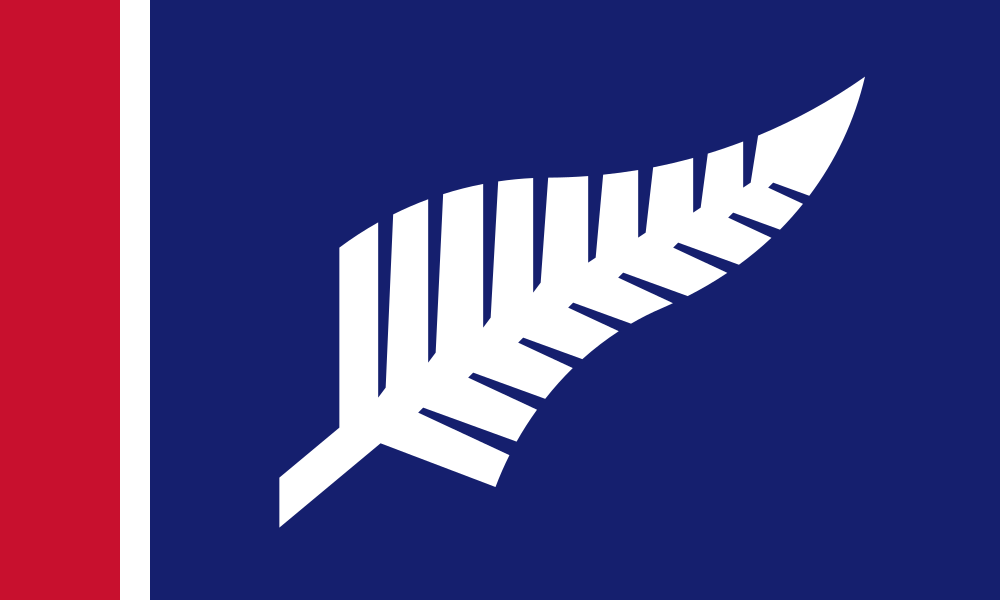

3.2 Silver Fern with Red Stripe

This one was also quite popular. This was James’ personal favourite out of our designs – he felt it was “simple but not boring or an overdone layout”. This used to be the only design published on this website, and someone e-mailed me out of the blue just to tell me that he loved it and supplied a link to the government’s submission form because he wanted me to submit it so badly.

Silver Fern with Red Stripe

Mock-ups for Silver Fern with Red Stripe

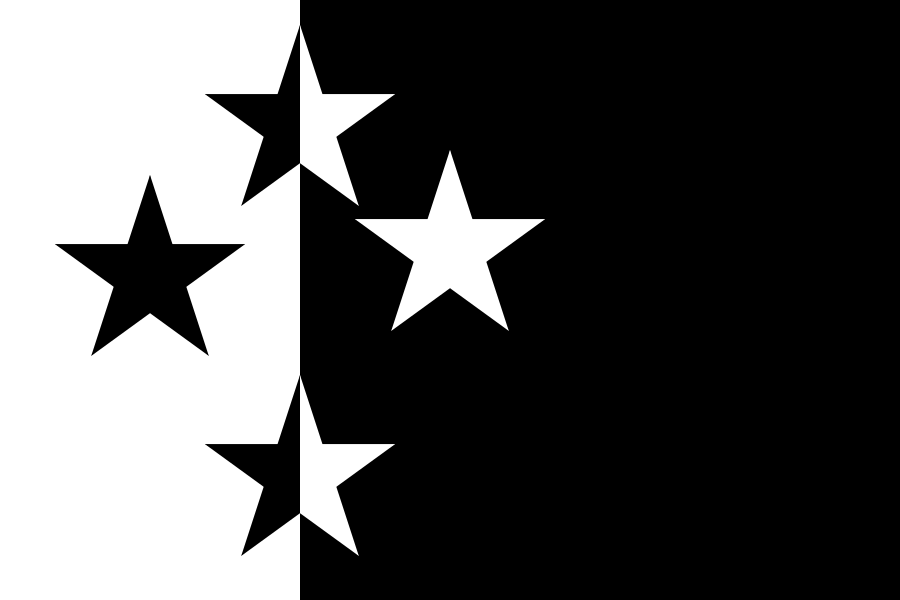

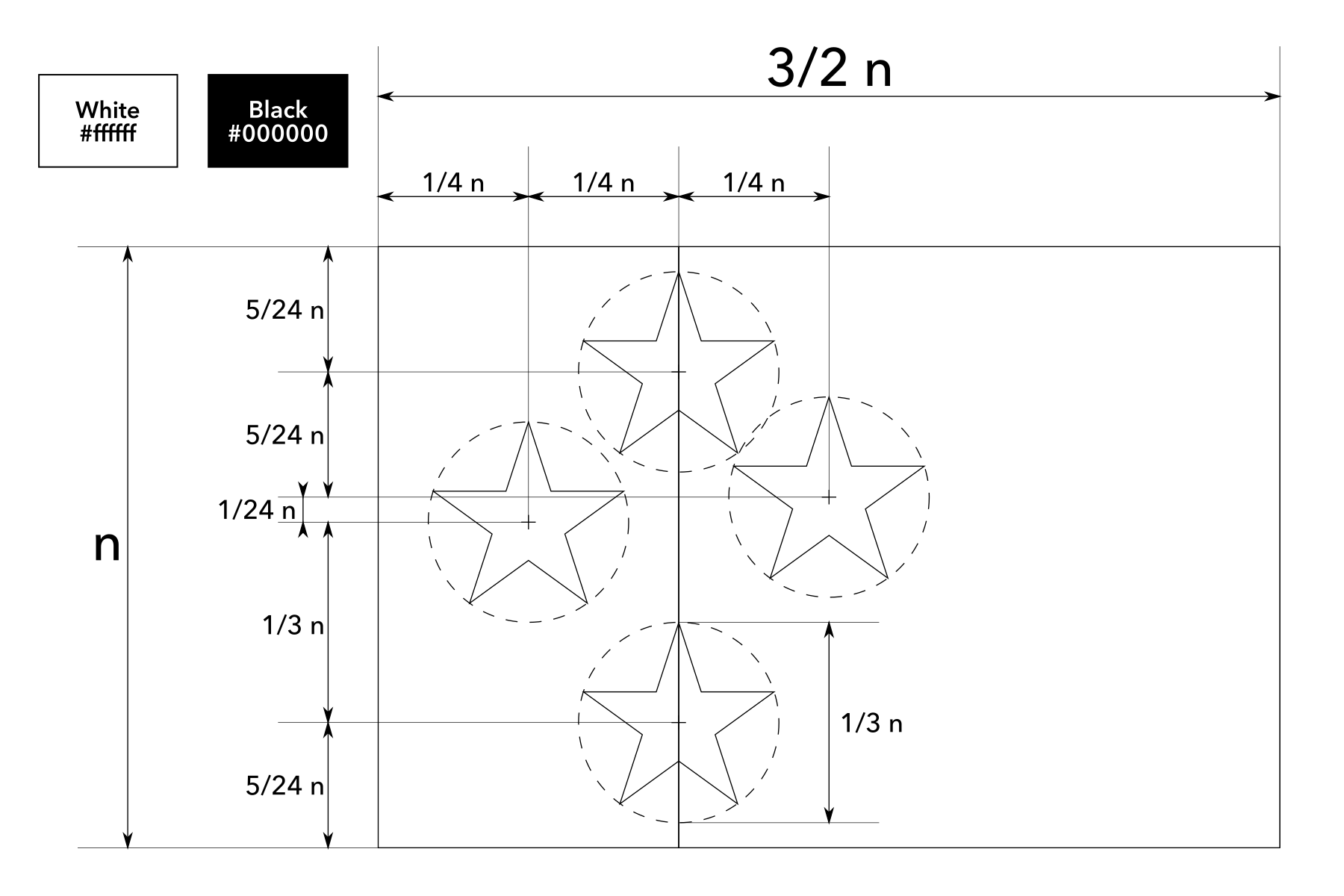

3.3 Yin-Yang

Yin-Yang was created in 2024 and is the most recent design in our selection. It’s also the oddest, as it’s the only option with a purely black and white colour scheme and counter-changing.

Black represents the boundless night sky and white represents the land of the long white cloud. The southern cross represents our location and history. The counter-changing of black and white represents the embrace of opposites to shine as one – humanity and nature, residents and newcomers, North Island and South Island, different cultures, genders, sexual orientations, etc.

Yin-Yang

Mock-ups for Yin-Yang

Construction sheet for Yin-Yang

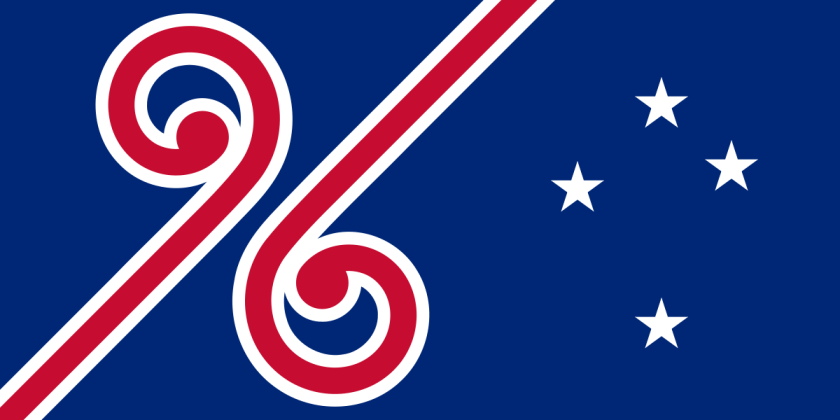

3.4 Flourishing Together

This design was the result of James’ conscious attempt to strongly counterbalance my personal style with his own. It uses a long aspect ratio with more complex and free-form patterns, although I still simplified the design in the years since he designed it.

By usual standards of success, this flag is actually the best of our designs – it is aesthetically charming, got enthusiastic responses, satisfies many aspects of national symbolism and scored highly in memory testing. However, by our guiding principle of maximum feasibility, we could not treat this as one of our “main” design proposals; it was clear that for a lot of the population, this design would veer a little too much into the “cheesy souvenir” trap.

This is the direct counterpart to my Australian flag proposal Dotted Sun and Stars.

Flourishing Together

Mock-ups for Flourishing Together

Construction sheet for Flourishing Together

For reference, here was James’ original version of Flourishing Together from 2015:

Flourishing Together

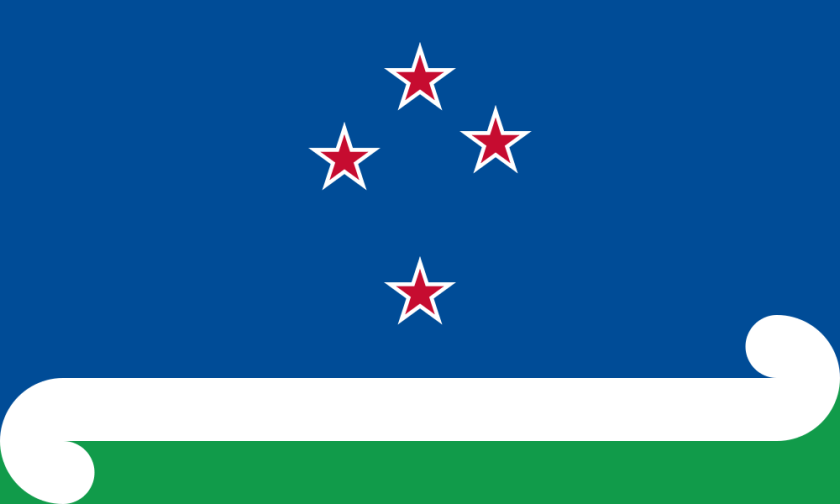

3.6 Land of the Long White Cloud (green)

This concept is the least popular of our designs, but is one of my personal favourites.

To our surprise, very few people recognised that overall layout was supposed to be a landscape where the white pattern is a koru representing the “land of the long white cloud”.

Land of the Long White Cloud (green)

Mock-ups for Land of the Long White Cloud (green)

Construction sheet for Land of the Long White Cloud (green)

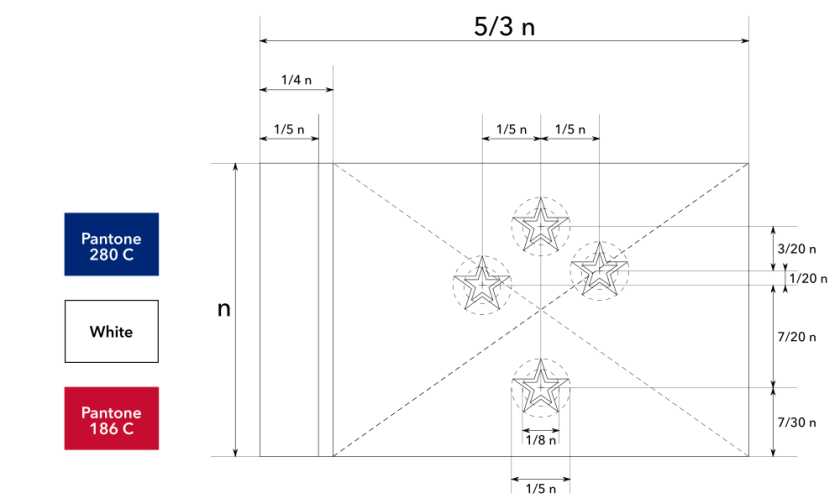

3.5 Southern Cross with Red Stripe

This is deliberately the most conservative of our designs. It came from an exercise to aim for cautiousness and tradition above all else.

However, it easily fell into the “it’s boring but it works” trap, which many people picked up on. Aesthetically, it doesn’t really have a good focal point either.

Southern Cross with Red Stripe

Mock-ups for Southern Cross with Red Stripe

Construction sheet for Southern Cross with Red Stripe

4. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to James Fitzmaurice for all his expertise and contributions to our designs.

Thanks to everyone who participated in our surveys. Thanks to everyone who conducted the research that helped us in our design process.

Waving flag mock-ups made with krikienoid’s Flag Waver software. Driver licence mock-ups contain licence design by New Zealand Transport Agency and painting of Lisa del Giocondo by Leonardo da Vinci. Digital icon mock-ups contain user interface elements from WhatsApp, Android Keyboard and Google’s flag emoji. We do not claim affiliation with nor ownership of the intellectual properties acknowledged in this section.

REFERENCES

Barrett, J. L., & Nyhof, M. A. (2001). Spreading nonnatural concepts: The role of intuitive conceptual structures in memory and transmission of cultural materials. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 1, 69–100.

Cheng, D. (2014). Flag debate: NZers favour new design – survey. Retrieved from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10625679

Davison, I. (2014). Kiwis back Union Jack flag. Retrieved from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11222086

Hubel, D. H., & Wiesel, T. N. (2004). Brain and Visual Perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Osborne, D., Lees-Marshment, J., & van der Linden, C. (2016). “National identity and the flag change referendum: Examining the latent profiles underlying New Zealanders’ flag change support.” New Zealand Sociology, 31(7), 19-47.

Sibley, C., Hoverd, W., & Duckitt, J. (2011). “What’s in a Flag? Subliminal Exposure to New Zealand National Symbols and the Automatic Activation of Egalitarian Versus Dominance Values.” The Journal of Social Psychology, 151(4), 494-516. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2010.503717

Sibley, C., Hoverd, W., & Liu, J. (2011). “Pluralistic and Monocultural Facets of New Zealand National Character and Identity.” New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 19-29.

Trevett, C. (2015). Flag poll message clear: Leave it alone. Retrieved from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11441353

When discussing proposed new New Zealand flags, I found myself drawn to two elements, the Koru and the constellation Matariki. There are no other national flags with either of those emblems, so it would be impossible to mistake for any other nation’s.

Thanks for your thoughts, Wesley.

Love your iteration of the silver fern flag — I think your creation of a slightly different version of the fern really did make it stick into my mind. I think a similar process could be observed in the Canada flag which may explain its popularity — as the maple emblem was common but normally in batches of three or with different points than on the final flag.

-Thomas D

Thanks for your feedback, Thomas. I drew inspiration from the design process of Canada’s iconic maple leaf, as documented in the book Our Flag: The Story of Canada’s Maple Leaf by Ann Maureen Owens. They started with a more complex rendering and learned to simplify it after wind tunnel testing.